Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario: 2025 Case Law in Review

The year 2025 proved to be a defining one for human rights adjudication in Ontario. Significant judicial review decisions from the Divisional Court, notable findings of sexual harassment and sex-based discrimination, important rulings on pregnancy-related protections, and major procedural reforms have reshaped the landscape for practitioners and self-represented applicants alike. This article examines the key decisions and developments, with an eye toward what they mean for those navigating the system in 2026 and beyond.

Part I: The Courts Push Back - Judicial Review Decisions

Perhaps the most striking development of 2025 has been the Divisional Court’s increased willingness to intervene when HRTO decisions fail to meet basic standards law, fact and procedural fairness. As Tribunal Watch Ontario has documented, the courts appear increasingly unwilling to defer to tribunal decisions that prioritize file closure over fair process. Several decisions stand out.

John v. Swedcan Lumican Plastics Inc., 2025 ONSC 3022

The Facts: The applicant filed a human rights application alleging employment discrimination on the basis of disability. In 2020, Vice-Chair Doyle denied the respondent’s request for a summary hearing and directed the matter to a merits hearing. That hearing commenced, and the applicant testified. The matter was then adjourned. In 2024, a different Vice-Chair (Tascona) ordered a summary hearing—making no acknowledgment that a merits hearing had already been directed and begun, and ultimately dismissed the application.The Divisional Court highklighted the main issue at paragraph 47 of its decision:

Most important here were the reasonable expectations of the applicant. Vice-Chair Doyle had denied the respondents’ request for a summary hearing and directed the matter to proceed to a merits hearing. That hearing was begun in 2020, and the applicant provided testimony. The case was then adjourned. In 2024, the Vice-Chair, as was his statutory prerogative, ordered a summary hearing. He made no acknowledgment that Vice-Chair Doyle had already refused such a hearing and directed a merits hearing, or that a merits hearing had been scheduled and begun, and the applicant had offered evidence. Counsel for the applicant raised concerns about the turn the case was taking in 2024 and sought to have the HRTO withdraw its decision to hold a summary hearing, highlighting the natural justice issue.

The Decision: The Divisional Court was sharply critical. The Court emphasized that procedural fairness requires that a litigant have the right to their day at the tribunal when that day has been granted, and that such a right cannot be “silently overruled by another adjudicator at the same level.” The application had created legitimate expectations that could only be satisfied by the merits hearing continuing to conclusion.

Key Takeaway: Once a merits hearing is directed and commenced, applicants have a reasonable expectation that it will proceed to conclusion. Practitioners should document procedural history carefully and be prepared to invoke the doctrine of legitimate expectations if the Tribunal attempts to redirect proceedings mid-stream. Additionally, the Divisional Court emphasized several times that the Applicant had objected to the change, therefore, objecting in writing is an important aspect of maintaining the record.

Ramirez v. Rockwell Automation Canada Ltd., 2025 ONSC 1408

The Facts: The applicant had no history of non-responsiveness throughout his HRTO proceedings. When he failed to respond to a single email from the Tribunal, the HRTO deemed his application abandoned and dismissed it.

The Decision: The Divisional Court found the dismissal “obviously unfair” (para 12). The Court stated plainly: “failing to respond to one e-mail, in all of the circumstances of this case, cannot possibly justify an inference that the Applicant had abandoned the proceeding” (para 8).

Key Takeaway: The HRTO cannot infer abandonment from a single missed communication, particularly where the applicant has otherwise engaged with the process. For applicants: ensure your contact information is current and respond promptly to all Tribunal correspondence. For practitioners: if your client faces dismissal for alleged abandonment, examine the full procedural history.

Konkle v. Ontario (Human Rights Tribunal), 2025 ONSC 4071

The Facts: The applicant filed a complaint against the Canada Games Council, reasonably believing the Canadian Human Rights Commission had jurisdiction. Six business days after being informed that the federal commission lacked jurisdiction, she filed with the HRTO, one day after the one-year limitation period had expired. The HRTO refused to extend the time, finding the delay was not incurred in good faith.

The Decision: The Divisional Court found the HRTO’s approach unreasonable. The Court held that “it is not a reasonable approach to require an accounting for every minute of every day of delay” (para 13). The relevant question was whether filing initially with the federal commission was a good-faith explanation for the delay, and whether the applicant moved with reasonable dispatch upon learning of the jurisdictional issue. She clearly had.

Key Takeaway: Jurisdictional confusion between federal and provincial human rights systems can constitute good faith delay. If you discover you have filed in the wrong forum, act immediately, and document your timeline meticulously. Consider filing in both forums if you are unsure and up against a limitation date.

Green v. Ontario (Human Rights Tribunal), 2025 ONSC 6223

The Facts: Matthew Green, a Black man and then Ward 3 Councillor in Hamilton, alleged that a Hamilton Police officer had subjected him to racial profiling during a wellness check in April 2016. Mr. Green was waiting at a bus stop, standing under an overpass to shield himself from the wind, when Constable Pfeifer stopped his cruiser and approached to conduct what he described as a "well-being check." Mr. Green filed complaints with both the Office of the Independent Police Review Director (OIPRD) and the HRTO. After a five-day Police Services Act disciplinary hearing, with viva voce evidence, cross-examination, and legal representation, the hearing officer found no discreditable conduct. Mr. Green then reactivated his HRTO complaint. The HRTO dismissed it under s. 45.1 of the Code, finding that the PSA proceeding had "appropriately dealt with the substance" of his complaint. The Tribunal denied reconsideration.

The Decision: The Divisional Court found the HRTO's decision unreasonable. Justice Sachs, writing for a unanimous three-judge panel, held that "the Tribunal failed to apply or reasonably engage with the decision by the Supreme Court of Canada in Penner v. Niagara (Regional Police Services Board) or with the HRTO jurisprudence since Penner. The HRTO has consistently applied Penner to find that it would be unfair to dismiss human rights complaints by operation of s. 45.1 based on findings in a PSA process. This rendered the decisions unreasonable" (para 5).

The Court emphasized that this was the first and only case since Penner where the HRTO had dismissed a human rights application under s. 45.1 because of a prior police disciplinary proceeding, a striking departure from the Tribunal's own established approach. Applying Vavilov, the Court noted that an administrative decision that "fail[s] to explain or justify a departure from a binding precedent in which the same provision had been interpreted" (para 39) may be unreasonable.

The Court further observed that the Supreme Court in Penner had found that allowing a PSA hearing to serve as the final word in civil proceedings is "a serious affront to basic principles of fairness" because the Chief of Police appoints the investigator, the prosecutor, and the hearing officer. Permitting this process to preclude a human rights complaint effectively allows the Chief to become "the judge of his own case" (para 31). A human rights complainant can seek no personal or systemic remedy in the PSA process, remedies that are central to the Code's purpose.

The Ontario Human Rights Commission intervened in support of Mr. Green's position. The matter was remitted to the HRTO to be heard by a different adjudicator.

Key Takeaway: The HRTO must engage meaningfully with binding precedent and its own established jurisprudence. Where the Tribunal departs from a consistent line of authority without explanation, the resulting decision is vulnerable to judicial review under Vavilov. For practitioners, Green confirms that police disciplinary proceedings do not preclude human rights complaints and that the policy rationales in Penner, particularly the structural unfairness of the PSA process and the unavailability of Code remedies, remain live considerations under s. 45.1. For applicants who have been through PSA proceedings, this decision is an important reassurance that the human rights process remains open to them.

The Dosu Decisions: Dosu v. Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, 2025 ONSC 6496 & 2025 ONSC 6509

The Facts: Ms. Dosu, a York University employee, filed an HRTO application alleging racial discrimination. The Tribunal dismissed most of her claims as time-barred. She sought judicial review, and both her union (YUSA) and the Black Legal Action Centre (BLAC) moved to intervene.

The Decisions: In a procedural anomaly, two different judges issued contradictory rulings on consecutive days. Justice Shore dismissed both intervention motions, characterizing the case as a narrow limitation issue. Justice Nakatsuru granted both motions, finding a “sufficient foundation” for BLAC’s involvement and emphasizing BLAC’s concern that the HRTO’s approach could effectively impose an internal-exhaustion requirement that would particularly harm Black applicants. Justice Nakatsuru recognized that BLAC was “well placed to offer assistance in how the intersectional nature of discrimination faced by Black persons should be addressed” (para 19).

The two contradictory rulings appear to have resulted from an administrative error in how the Divisional Court assigned the written motions. The intervention requests were filed under two different court file numbers: DC-25-00000498-00JR (before Justice Shore) and DC-25-00000489-00JR (before Justice Nakatsuru). Each judge appears to have decided the paper motions independently, unaware that the other was also seized of the identical question. As of this writing, there has been no reported resolution of the conflict, though Justice Nakatsuru's order, which contains specific terms for the intervenors' participation, appears to be the operative ruling.

Key Takeaway: The divergent outcomes highlight how judicial perspective can shape access to systemic arguments. For practitioners, the case underscores the importance of framing intervention requests around systemic implications and intersectionality. For advocacy organizations, Dosu represents both a cautionary tale and an opportunity to advance systemic analysis in human rights adjudication.

Part II: Sexual Harassment, Sex-Based Discrimination, and Gender-Related Cases

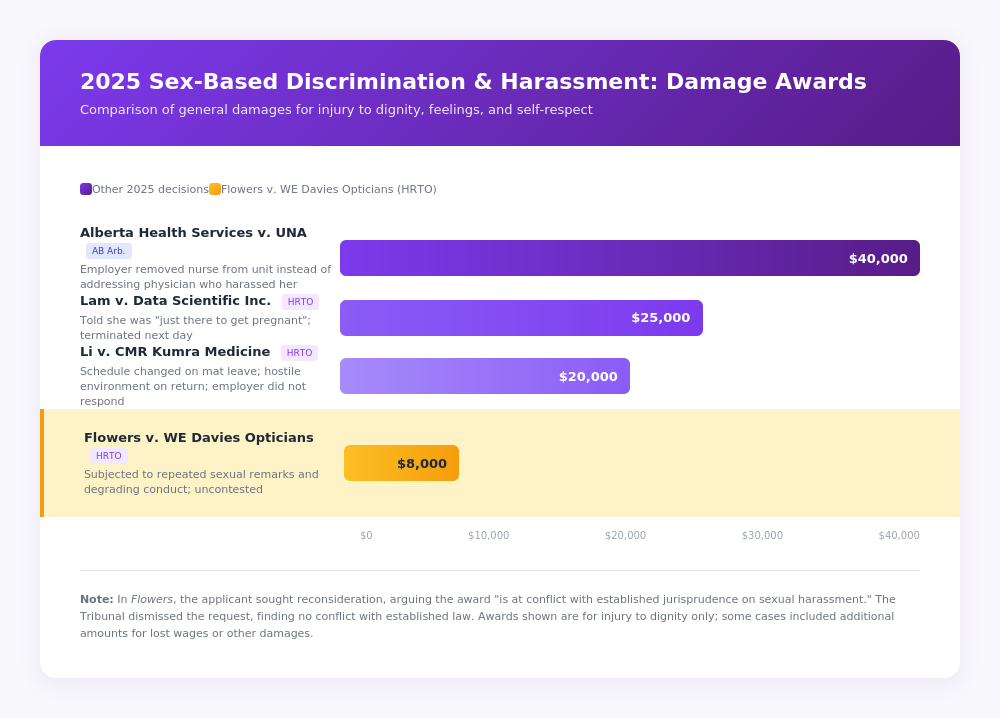

The 2025 jurisprudence includes several important decisions addressing sexual harassment, pregnancy discrimination, and the employer’s duty to maintain a workplace free from sex-based harassment. These cases reinforce that the Tribunal and arbitrators take these violations seriously and will award meaningful remedies when the evidence supports a finding of discrimination.

Li v. CMR Kumra Medicine Professional Corporation, 2025 HRTO 399

The Facts: A receptionist was notified by her employer, while on maternity leave, that her work schedule would be changed significantly, from four days a week for 30 hours to five days a week for 45 hours. Upon returning to work, she experienced a hostile work environment: the employer gave her increased job duties without adequate training, berated her in front of colleagues, and effectively replaced her with another employee. The employer failed to respond to the human rights application.

The Decision: The Tribunal found discrimination based on pregnancy and family status. The applicant was awarded nearly $45,000 in total compensation, including damages for injury to dignity, feelings, and self-respect, plus lost wages.

Prior to filing at the HRTO, Ms. Li had pursued an employment standards complaint with the Ministry of Labour. The Employment Standards Officer concluded she had been constructively dismissed and awarded $6,188 in termination pay, but explicitly declined to address her human rights concerns, stating they were outside the scope of the ESA and that she was “fully within her rights to pursue a claim with the Human Rights Tribunal" (para 22). The Tribunal found that because the ESO refused to engage with the Code issues and directed her elsewhere, section 45.1 did not apply to bar her HRTO application.

The decision affirmed the HRTO’s remedial authority to award damages even where the respondent does not participate and confirmed that remedies can be pursued in multiple forums provided another proceeding has not appropriately dealt with the substance of the Code violations.

Key Takeaway: Employers cannot unilaterally impose significant schedule changes on employees returning from parental leave without engaging in the accommodation process. Non-participating respondents face adverse findings based on uncontested evidence. This decision reinforces the serious harm caused by pregnancy discrimination and the protections owed to pregnant workers and new parents.

Lam v. Data Scientific Inc., 2025 HRTO 2813

The Facts: A graphic designer disclosed her pregnancy and inquired about benefits and pregnancy leave. She was told she “was just there to get pregnant and [would] never come back” (para 15) and was terminated the following day. She had also been placed on a six-month probation and had her work questioned because she was from Hong Kong.

The Decision: The Tribunal found discrimination based on pregnancy and place of origin, as well as harassment, including sexual harassment. The applicant was awarded $25,000 for injury to dignity, feelings, and self-respect, approximately $4,600 for lost income, and $1,500 for medical expenses.

Key Takeaway: Pregnancy-related terminations remain an area where the Tribunal continues to find discrimination when the evidence supports it. The temporal proximity between disclosure and termination was significant. Applicants should document the timeline carefully, including any discriminatory comments made around the time of disclosure.

Alberta Health Services v. The United Nurses of Alberta, 2025 CanLII 74910

The Facts: A registered nurse experienced sexual harassment by a physician. Rather than addressing the physician’s conduct, Alberta Health Services removed the nurse from her unit. The nurse grieved, alleging the employer had failed to provide a safe workplace and had discriminated against her.

The Decision: The arbitrator ordered Alberta Health Services to pay $40,000 in general damages to the nurse, finding AHS had failed to provide a safe workplace and discriminated against her following the sexual harassment. The decision concluded AHS breached both its occupational health and safety obligations and its duty to accommodate by removing the nurse from her unit instead of imposing consequences on the harasser.

Key Takeaway: Although this is an Alberta arbitration, the principles are directly applicable in Ontario: employers cannot discharge their duty to provide a harassment-free workplace by penalizing the complainant rather than addressing the harasser's conduct. The decision is particularly relevant where the harasser is a physician, client, or other third party over whom the employer claims limited control. Removing the complainant rather than taking action against the perpetrator can itself constitute discrimination and a breach of the employer’s duty to provide a safe workplace. This decision sends a clear message that the victim should not bear the consequences of another’s misconduct.

Flowers v. WE Davies Opticians, 2025 HRTO 2336 & 2025 HRTO 2658

The Facts: The applicant, an employee at an optical business, was subjected to persistent sexualised conduct by the owner, who was the sole director of the corporate respondent. She was called "f**kable" in the workplace. The owner grabbed his own crotch in front of her. The respondents did not appear at the hearing, leaving this evidence entirely uncontested.

The Decision: The Tribunal found the employer and its sole director jointly and severally liable for sexual harassment, sexual solicitation, and creating a poisoned work environment. The applicant was awarded $8,000 for injury to dignity, feelings, and self-respect.

The applicant sought reconsideration, arguing through counsel that the damage award "is at conflict with established jurisprudence on sexual harassment and sexual solicitation" and that the decision "leaves vulnerable the Code-protected rights of victims of sexual harassment and solicitation in the workplace" (para 16). The Tribunal dismissed the reconsideration request, finding no conflict with established jurisprudence and declining to find that any factors outweighed the public interest in finality.

Key Takeaway: The Tribunal's position that an $8,000 award for uncontested evidence of explicit sexual remarks and crude sexualised conduct does not conflict with established jurisprudence deserves scrutiny. Compare Alberta Health Services, where an arbitrator awarded $40,000 to a nurse whose employer responded poorly to harassment by a third party, or Lam, where the Tribunal awarded $25,000 for pregnancy-related comments and next-day termination. Here, where an employer called a worker a sexually explicit name and engaged in lewd behaviour directly in front of her, and then failed to even contest the allegations, the Tribunal valued that harm at $8,000 and found no basis for reconsideration. Practitioners should be aware that HRTO damage awards for sexual harassment remain highly variable, and survivors should understand that even clear and uncontested evidence of serious misconduct may result in awards that do not reflect the gravity of what they experienced.

Part III: Other Notable Findings of Discrimination

Against the backdrop of high dismissal rates, several 2025 decisions found discrimination based on disability and awarded meaningful remedies.

Frankcom v. DECAST Ltd., 2025 HRTO 2602

The Facts: The applicant suffered three workplace injuries between 2018 and 2019. He alleged that his employer failed to accommodate his disability and subjected him to workplace harassment before terminating his employment. The WSIB had previously rejected his claims, finding the termination unrelated to his workplace injury.

The Decision: The HRTO refused to dismiss the application, ruling that WSIB and HRTO proceedings address different legal questions. WSIB determinations focus on entitlement to benefits; the HRTO examines whether conduct constitutes discrimination, harassment, or reprisal under the Code. The application was permitted to proceed.

Key Takeaway: WSIB findings do not preclude HRTO applications. Employers cannot rely solely on favourable WSIB outcomes to defend against human rights complaints. The continuing series doctrine may apply where accommodation and harassment issues span multiple incidents over time.

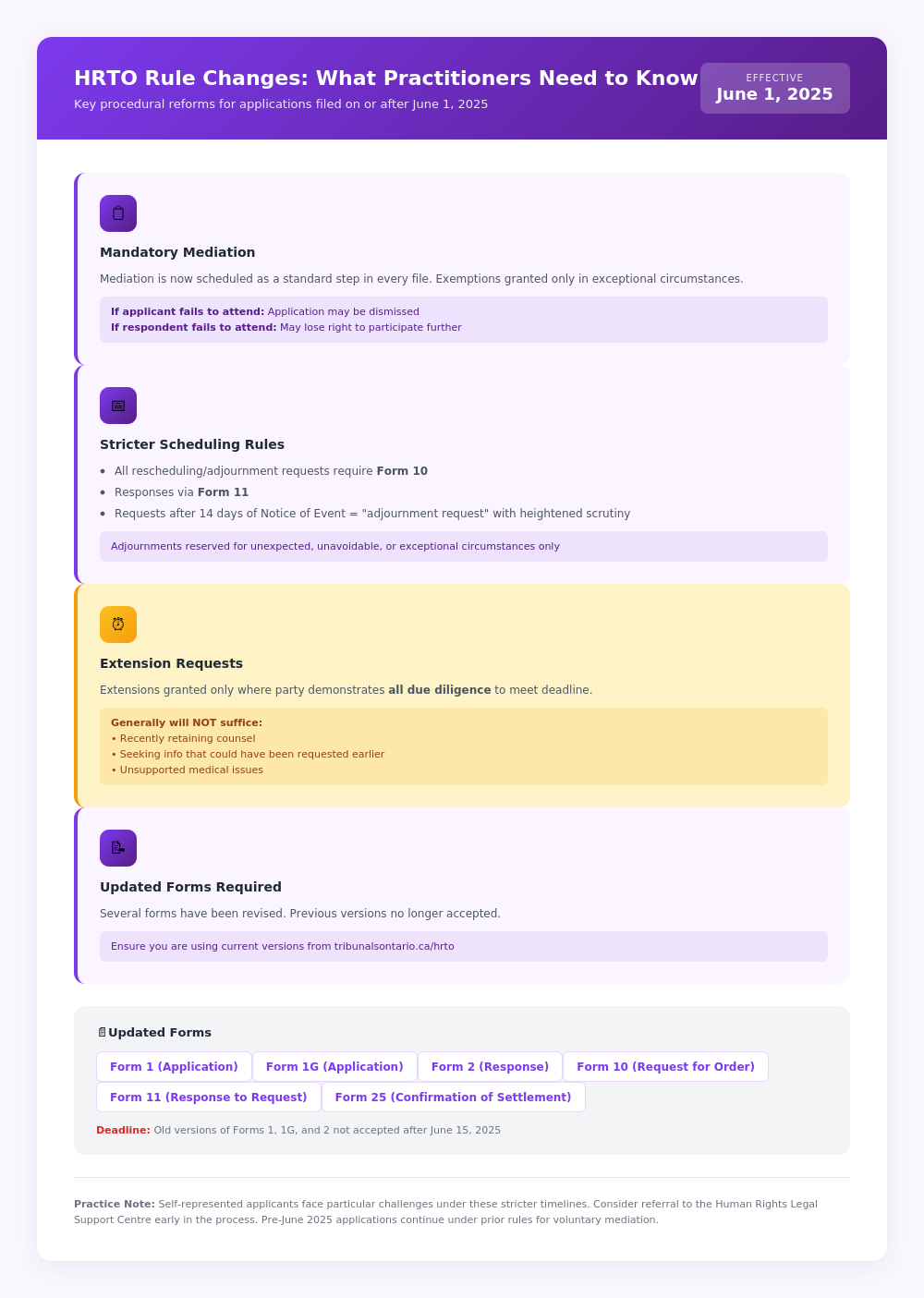

Part IV: The June 2025 Rule Changes

Effective June 1, 2025, the HRTO introduced significant procedural reforms designed to address its substantial backlog and streamline proceedings.

Mandatory Mediation: For all applications filed on or after June 1, 2025, mediation is now mandatory. The Tribunal will schedule mediation as a standard step in every file, with exemptions granted only in exceptional circumstances. Failure to attend carries consequences: applications may be dismissed if applicants fail to attend, and respondents may lose the right to participate further if they fail to attend.

Stricter Scheduling Rules: Rescheduling and adjournment requests now require completion of Form 10, with responses via Form 11. Requests made after 14 days of a Notice of Event become “adjournment requests” subject to heightened scrutiny. Adjournments will be reserved for unexpected, unavoidable, or exceptional circumstances.

Extension Requests: Extensions will only be granted where the party demonstrates they acted with all due diligence to meet the deadline. Reasons such as recently retaining counsel, seeking additional information that could have been requested earlier, or unsupported medical issues will generally not suffice.

Updated Forms: Forms 1, 1G, 2, 10, 11, and 25 have been revised. Older versions are no longer accepted as of June 15, 2025.

Assessment: The mandatory mediation requirement reflects the reality that most files already settle at mediation. However, the stricter scheduling and extension rules will disproportionately affect self-represented applicants who may lack the resources or knowledge to meet accelerated timelines. Practitioners should adapt their practice to assume mediation preparation as a standard component of every file, and clients should be counselled early about the consequences of non-attendance.

Part V: Reflections for Practitioners and Self-Advocates

Several themes emerge from the 2025 jurisprudence.

First, the Divisional Court is increasingly willing to intervene when the HRTO prioritises efficiency over fairness. The John, Ramirez, Konkle, and Green decisions collectively signal that courts are attentive to the serious consequences of unfair dismissals for claimants who are often among the most vulnerable residents of Ontario.

Second, judicial review remains a critical avenue for correcting procedural errors. Practitioners should be prepared to pursue JR when HRTO decisions reflect inadequate reasoning, failure to engage with binding precedent, or obvious procedural unfairness. The Vavilov standard of reasonableness is being applied with rigour in these contexts.

Third, the 2025 sexual harassment and sex-based discrimination decisions demonstrate that tribunals and arbitrators will hold employers accountable for failing to maintain workplaces free from harassment. The Alberta Health Services decision is particularly significant: when harassment occurs, the employer must address the conduct of the harasser, not penalize the victim.

Fourth, pregnancy and family status protections remain robust. The Li and Lam decisions reinforce that employers cannot impose adverse consequences on employees because of pregnancy or parental leave. Temporal proximity between pregnancy disclosure and adverse treatment continues to be significant evidence of discrimination.

Fifth, the Dosu decisions remind us that systemic arguments and intersectional analysis remain contested terrain. Advocacy organisations and applicants should continue pressing for these frameworks, recognising that outcomes may depend significantly on which judge hears the matter.

Sixth, the June 2025 rule changes represent a fundamental shift in HRTO practice. Mandatory mediation, stricter timelines, and formal procedural requirements will require adaptation from all parties. Self-represented applicants face particular challenges and should seek assistance from the Human Rights Legal Support Centre early in the process.

Seventh, the Green decision raises a concern that extends beyond its particular facts. The Divisional Court found that the HRTO had departed from binding Supreme Court of Canada authority and from the Tribunal's own consistent post-Penner jurisprudence, without explanation or justification. This was not a case of procedural unfairness or administrative error; the Court found that the Tribunal had failed to correctly apply the law. That the HRTO could dismiss an application on grounds that contradicted both binding precedent and its own established approach suggests a need for greater attention to legal consistency in Tribunal decision-making. Practitioners pursuing judicial review should be alert to this possibility: where an HRTO decision departs from settled law without acknowledging or distinguishing the relevant authorities, Vavilov provides a clear basis for intervention. The Court's willingness to correct such errors, and to remit matters to different adjudicators, signals that reasonableness review has teeth when tribunals fail to engage with the jurisprudence that constrains them.

Conclusion: The System Remains Worth Using

The 2025 case law presents a complex picture. The HRTO faces significant challenges: backlogs, procedural reforms of uncertain effect, and judicial criticism for unfairness in some dismissals. Yet the system continues to find discrimination when the evidence supports it, courts continue to correct errors, and procedural reforms aim to resolve matters more efficiently.

For those who have experienced discrimination, the message should not be discouragement. Human rights law advances through the claims of individuals willing to assert their rights. The decisions reviewed here, both the victories and the reversals, contribute to the ongoing development of protections under the Code. Seek legal advice early. Document everything. Understand the procedural landscape. And know that the assertion of your rights matters.

Nicole Biros-Bolton is the Principal Lawyer at Bird Bolt Law Professional Corporation in Hamilton, Ontario, practicing in employment law, human rights, and Charter litigation. She can be reached at www.birdboltlaw.com.

Appendix: 2025 Cases Referenced

Judicial Review Decisions

John v. Swedcan Lumican Plastics Inc., 2025 ONSC 3022

Ramirez v. Rockwell Automation Canada Ltd., 2025 ONSC 1408

Konkle v. Ontario (Human Rights Tribunal), 2025 ONSC 4071

Green v. Ontario (Human Rights Tribunal), 2025 ONSC 6223

Dosu v. Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, 2025 ONSC 6496

Dosu v. Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, 2025 ONSC 6509

Sexual Harassment, Sex-Based Discrimination, and Gender-Related Cases

Li v. CMR Kumra Medicine Professional Corporation, 2025 HRTO 399

Lam v. Data Scientific Inc., 2025 HRTO 2813

Flowers v. WE Davies Opticians, 2025 HRTO 2336 & 2025 HRTO 2658

Alberta Health Services v. The United Nurses of Alberta, 2025 CanLII 74910

Other Discrimination Findings

Frankcom v. DECAST Ltd., 2025 HRTO 2602